"Houston, Tranquility Base Here. The Eagle has Landed."

Published Jul 03, 2019 by Josh Pherigo

The First Word

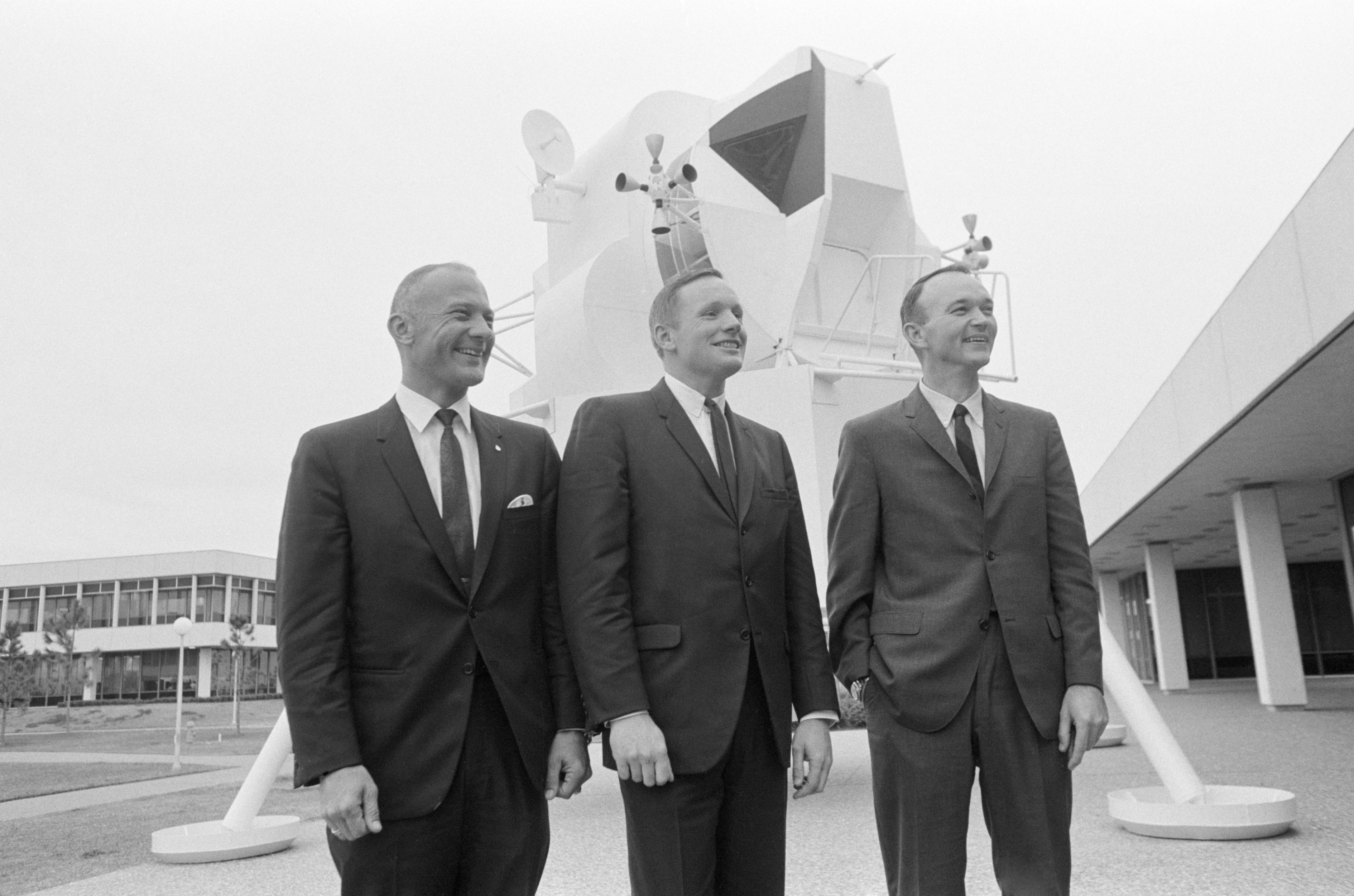

When the struts of the Apollo 11 Lunar Module met the powdery surface of the Moon on July 20, 1969, Commander Neil Armstrong marked the arrival with an eight-word message back home.

“Houston,” Armstrong said. “Tranquility base here. The Eagle has landed.”

The time was 3:17 p.m. at mission control – four days, six hours and forty-six minutes after liftoff and more than eight years after President John F. Kennedy first challenged America to aim for the moon. The Apollo 11 crew had traveled 240,000 miles from Earth aboard the most complex machine ever conceived – guided by the most sophisticated computers ever built and boosted by the most powerful rocket ever launched – only to come within 30 seconds of running out of fuel.

“Roger, Tranquility. We copy you down,” came the reply from Charlie Duke in mission control. “You got a bunch of guys down here about to turn blue.”

On Earth, more than half a billion people watched as the moon landing unfolded in real-time. For Americans, it was a staggering victory of science and technology, the fulfillment of a mammoth national effort to accomplish humanity’s greatest-ever journey. For Houstonians, it was personal.

No city did more to put men on the moon, and no city took more pride in its accomplishment.

At the executive committee meeting of the Houston Chamber of Commerce (predecessor to the Greater Houston Partnership) the morning after the landing, chamber president E. Clyde McGraw described the “extremely thrilling” events of that week and pointed out that a local newspaper columnist observed that “Houston” had been the first word spoken from the moon.

“Every mission points up even more Houston’s close identification with the manned space program,” McGraw said.

As the center of gravity for the U.S. space program, the Manned Space Center (renamed Johnson Space Center in ’73) oversaw every facet of the planning, design, training and execution of the Apollo moon missions. It was, quite literally, at the center of a worldwide communications network designed specifically to control and monitor the moon missions. On the day of the Apollo 11 landing, a 2-million-mile web of underground and ocean-laid cables connected Houston to radar and antenna stations across the globe – an unprecedented feat at the time.

From Houston, engineers helped invent the techniques and procedures necessary to make deep space flight possible, and mission planners tediously orchestrated the work of more than 20,000 NASA contractors across the country. At the height of its activity the Apollo program employed more than 500,000 Americans at an annual cost of $4 billion (equivalent to $32 billion today). The burden of managing that massive effort, keeping those moving parts aligned and on scheduled fell largely on the shoulders of Houston residents, as did the job of actually flying the missions.

Fifty years after Apollo 11’s historic landing, no city has so emphatically embraced its lunar legacy like Houston. We named our sports teams and our theme parks after space iconography; worked NASA designs into our architecture and our community spaces, painted it in murals across our buildings; we adopted the nickname “Space City” with pride. But years before we could lay claim as the first word spoken from the moon, Houston was just one of 20 cities vying for a government construction project – the HQ2 of its day.

Why Houston?

By the fall of 1961, the U.S. had fallen badly behind the Soviets in the race for space supremacy. Though both nations had completed two manned missions apiece, NASA had yet to put an astronaut in orbit, a critical feat the Soviets achieved on the very first manned flight in April. Worse still: the short, parabolic arcs of NASA’s first two Mercury flights had lasted just 15 minutes each. America’s space program had less than half-an-hour of manned flight under its belt - fewer than 10 minutes in zero-gravity. The Soviets, on the other hand, had amassed a staggering 27 hours of flight time in their first two missions (it would take the U.S. another two years to accumulate that amount).

President Kennedy had recognized early on that in the high-stakes context of the escalating Cold War, outer-space was the newest battlefield. That spring Kennedy had pushed Congress for a massive increase in space funding, deeming it a defensive necessity (NASA’s budget would double by ‘63 and quadruple by ‘65), and for the first time, Kennedy laid out his charge for the U.S. to achieve a moon landing “before the decade is out.”

To get there, NASA would need a new, dedicated campus capable of housing the sprawling apparatus required to develop the science and techniques making a moon mission possible. That’s the charge NASA site selectors carried to Houston in late August 1961. Houston was one of at least 20 cities under consideration for the Manned Space Center, a $60 million facility ($480 million in today’s money) that would employ 3,000 government workers and serve as the lynchpin for the entire space program. The prospect of such an economic injection had local leaders salivating.

Houston Chamber of Commerce President P. H. Robinson, who met with NASA’s site selection team during their visit, promised that the Chamber was “available to furnish whatever assistance needed,” as the evaluators did their work. NASA’s specific requirements for the new site included the nearby presence of a large and skilled labor force, access to deepwater transportation routes and a nearby airport, reasonable local building costs, a reliable electric and communications grid, and the availability of temporary office space to house NASA staff while the manned space center was under construction.

The space agency was in a hurry, and they didn’t have to wait long.

On Tuesday, September 19, 1961, three weeks after the Houston site visit, NASA administrator James Webb announced that a cattle pasture near the farming town of Clear Lake, 25 miles southeast of downtown Houston would become the permanent site of NASA’s manned space center – home to mission control and the nation’s astronaut corps. NASA officials said the Houston region and the site itself - a 1,300-acre section of land mostly owned by Rice University - met each of the agency’s 14 requirements, beating out competing cities like Corpus Christi and San Diego.

It helped that Houston had a couple of political aces up its sleeve. Legendary local businessman and LBJ loyalist George R. Brown, whose construction firm Brown and Root would eventually build much of the Manned Space Center, took an active interest in the direction of the space program from its infancy. When Kennedy, in the spring of ‘61, asked Vice President Johnson to recommend a course forward for the space program – an effort that generated the moonshot goal – Brown was one of only a handful of civilians invited to participate in a closed-door strategy session in Washington. As the chair of Rice University’s board of regents, he facilitated the deal that would provide land for the Space Center. Humble Oil Company (now ExxonMobil) had donated 1,000 acres to Rice years before for the express purpose of serving as a space research center. Rice, in turn, simply donated the land to NASA.

The other leading force in Houston’s corner was Texas Congressman Albert Thomas. As chair of the appropriations committee, the powerful congressman is credited with steering the selection toward Houston. Taking a hands-on approach, he personally hosted the NASA site selectors around Houston during their August fact-finding mission, later assuring Chamber president Robinson that Houston had a “good chance” of winning the bid. The morning of the announcement, it was Thomas who first phoned Robinson with the good news.

Upon hearing the news, the chamber execs were fired up. Straight away, the chamber’s vice president Marvin Hurley ordered “1,000 copies of material related to Houston” airmailed to NASA headquarters in Virginia for distribution to the relocating employees, according to the minutes of the executive committee meeting that day.

The October edition of Houston magazine, a publication of the Chamber, trumpeted the arrival of the forthcoming “Space Lab” which it said would include “an enormous domed structure, which can contain a space capsule one-third as tall as the San Jacinto Monument.” The facility’s 3,000 employees, the article said, would draw a payroll more than $17 million per year ($136 million today), not counting the many outside firms supporting NASA’s work.

Within weeks, the first wave of NASA employees had already arrived, setting up temporary headquarters in offices around the city. And more were on their way.

Learn how Houston continues to develop new paths of innovation and get details on the Houston Spaceport, which will be the largest urban spaceport of its kind.

The Houston Report

The Houston Report